What is interferometry?

For a long time I’ve been meaning to use this blog as a way of explaining my ongoing research interests to my friends who may or may not be astronomers. As I’m coming up on my first-year PhD confirmation, I’m reflecting on everything I’ve learned in the past year. As a way of procrastinating writing my confirmation report, I thought I’d sit down and write up an explanation of the technique I have been learning for much of my PhD so far: interferometry. Perhaps the visuals I’ve made may come in handy for my confirmation too.

So far my PhD focus has meandered through some different roads, but they all have led to a somewhat common destination: looking to map the surfaces of stars and planets, especially looking at what we can learn about them from detailed observations of their rotation. So I’ve been aiming to measure the shapes and even surface features on stars to see evidence of rotation. Even the most nearby stars are incredibly far away. This means that stars from our perspective are tiny–in fact it’s usually safe to assume stars are virtually point-like sources of light. However, in trying to push the magnifications achievable and actually resolve the surfaces of stars, it’s hard to beat an interferometer. An interferometer is a combination of several individual telescopes that tries to achieve the resolving power, or magnification, of a single telescope, often much larger than would be feasible to build.

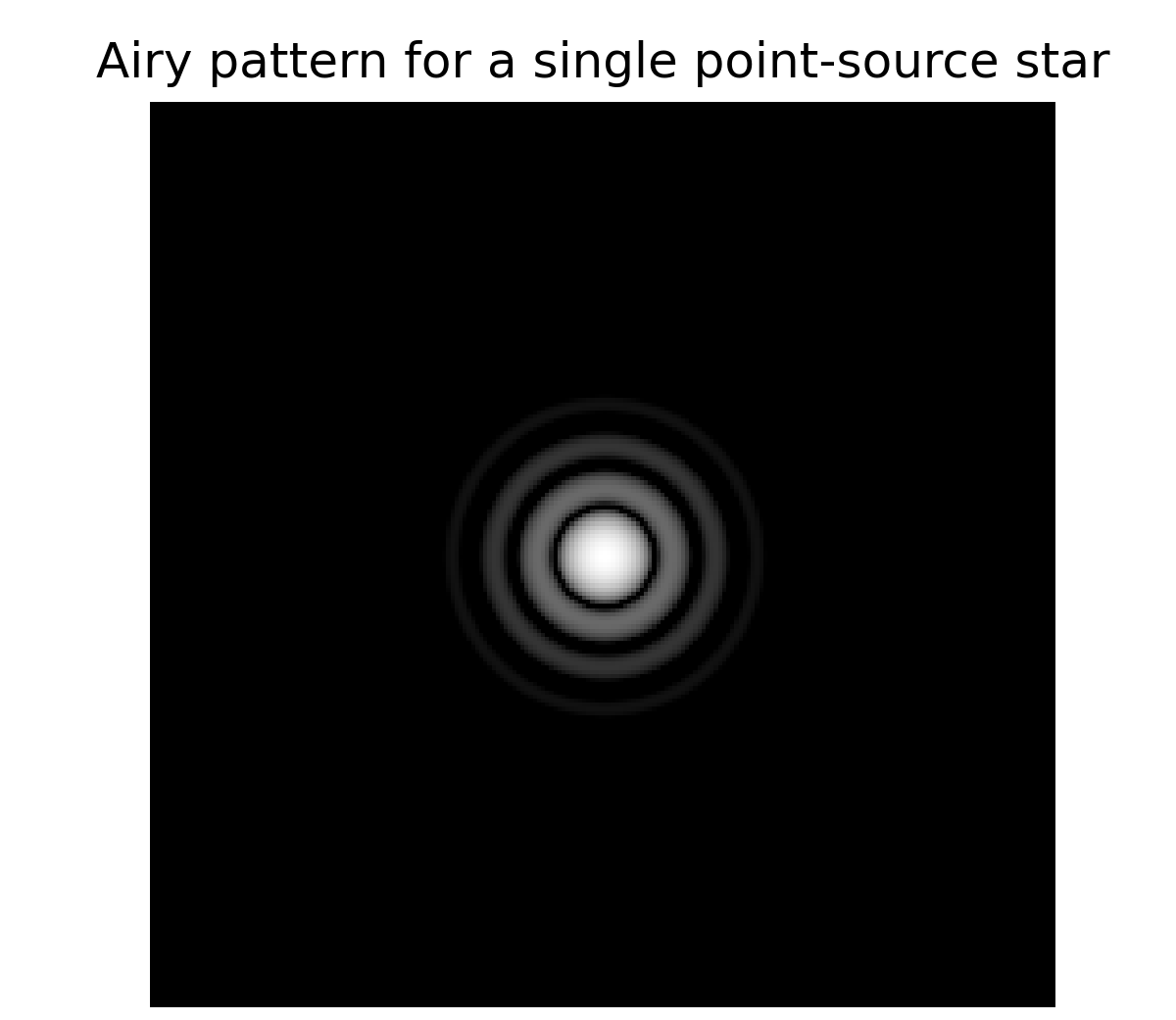

A note before I start: I will try not to delve into the wave nature of light and why it produces interference patterns here that it does. Astronomers may be familar with patterns like the Airy disk, and physicists might be more familiar with interference fringes. I’ll take it as a given that these patterns are produced because I want to focus on how we use the shapes of these interference patterns to our advantage, but I plan to write a prequel explainer on why we get these patterns to begin with.

The resolution limit:

To understand how an interferometer works, we must first understand how a regular telescope works, and explore a fundamental limit to the amount we can magnify with a given telescope.

When I first starting learning to use a telescope, I learned that it was not the telescope itself that magnified the image, but the eyepiece, and it was important to buy eyepieces with a variety of magnifications to see objects big and small. For me however, this begged the question of why anyone even needed a big telescope to see small detail–why couldn’t you just buy an eyepiece with an arbitrarily high magnification? The same concept extended to cameras mounted on a telescope–having more pixels on your camera should correspond to being able to see finer details. Instead of making larger telescopes, why not just make a really pixel-dense camera? The answer, I later learned, was not a technological limitation but a fundamental physics one–related to the wave nature of light.

If you point a telescope at a sufficiently distant, point-like star at a high magnification, what you see is not a perfect point of light but a pattern called an Airy disk. Due to the wave nature of light, even a perfectly point source star produces these concentric rings as seen below.

This is actually what sets the resolving, or magnifying power of a telescope. If we take an example (which we will use again later!) of a binary star for which we want to observe both stars, we can see that for a given telescope, if we reduce the separation between the two stars, there will be a point where they are indistinguishable from a single star, as their Airy patterns overlap. Extending this idea to, say, a planet, this means that any features smaller than a certain size will simply not be visible through that telescope, no matter how much you magnify the image.

Larger telescope have finer Airy patterns, and so can resolve finer details. The larger the diameter of the circular opening, or aperture of a telescope, the better its ability to resolve fine details.

More than one aperture:

Bigger is always better when it comes to telescopes. But, from above, we can actually calculate the size of the telescope we’d need to be able to resolve details on a given star. A relatively nearby, bright star observable with the unaided eye might span 1 milliarcsecond in diameter (where 1 degree –> 60 arcminutes–> 60 arcseconds –> 1000 milliarcseconds). To resolve such a star using visible light, we’d need a telescope with a diameter well over 100 meters! Our largest telescopes today are about 10 meters in diameter, so we are very far from being able to resolve even nearby stars with the largest telescopes! Perhaps with an OWL (Overwhelmingly Large Telescope), we could do this, but certainly not in the forseeable future.

Interferometry posits another way of achieving such high resolutions using manageably sized telescopes, with some tradeoffs. Let’s suppose we had two 1 meter telescopes spaced apart, and we sent the beams of light from each telescope through a tube to meet at a camera sensor in the middle. What would we see? The animation below shows that, as we smoothly transition from a single OWL telescope to two small telescopes, we see fringes that grow increasingly closely spaced as we increase the separation between the two telescopes. When the separation of our telescopes reaches the diameter of the OWL telescope, the fringes are so finely spaced they are comparable to the Airy pattern on an OWL telescope.

Seeing a fringe pattern like this presents its drawbacks though–although there is maybe some information of what’s in the sky, we don’t really see a traditional image like we would expect.